The following post coordinates my ongoing interest in sound studies with text analysis in the digital humanities. It seeks to draw an analogy between a compositional practice loosely defined as spectral music and large-scale data collection to interrogate textual ‘noise’ — and literary critics’ subsequent deafness to that noise. On the basis of this alignment, I work to suggest new ways of counting the material medium of text as a meaningful set of data.

– Noisy silence –

Listening and hearing. I can hear the hum of my computer if I turn my attention away from iTunes. The former helps create a space in which I can concentrate on the latter but in doing so passes by unnoticed. One is an aural context, the other, auditory recognition. A good deal of work in sound studies attends to this distinction. At times we forget that what we call ‘listenable’ is inscribed in a space, an institution, specific intentionalities, even our own bodies. The same goes for listening. “The scandal of contemporary hi-fidelity,” John Mowitt writes, “is not that one cannot actually hear it, but that we persist in regarding the perfection of listening as essentially beyond all forms of social determination” (215). The full spectrum of what we can hear often reveals those determinations — and what they leave out. Haunted spaces emerge when one listens to what one hears.

John Cage’s 4’33’’ said as much in 1952 when David Tudor sat at his piano in Woodstock, New York and closed the keyboard lid. No music was played, and surely the auditorium was quiet, but still there were things to hear — coughs, the rustle of clothes, shifting seats. There’s no such thing as silence; we audiophiles have simply developed band-pass filters in place of ears and block out the noise, much like the requisite “unseeing” the crosshatched cities Besźel and Ul Qoma force upon their citizens in China Miéville’s The City & the City. “The dominant, continuing search for a noiseless channel,” as Rosa Menkman puts it, “has been — and will always be — no more than a regrettable, ill-fated dogma” (The Glitch Moment(um) 11).

Spectral music does John Cage one better and blurs the edges between noise and note, turning scales into spectra and finding timbres the ear alone can’t register. Its composers share the central belief that “music is ultimately sound evolving in time,” simply “a special case of the general phenomenon of sound” (Fineberg 2). Through their application of acoustics and psychoacoustics to compositional practice they elide the distinction 4’33’’ makes between arrangement (albeit ‘silent’) and aural atmosphere. There are spaces and sounds in between the twelve notes of a Western octave: that “tonal system is governed by a set of harmonic rules that embody a compromise between the will to modulate among keys, the system of symbolically notating music, the available set of instruments, certain laws of acoustics, as well as many other concerns,” including the perceptual limits of our own ears (Pressnitzer and McAdams 33). Computationally-driven fast Fourier transformations deconstruct the chimerical idea of a stable “sound object,” a pure tone, and demonstrate that what we end up hearing, and in some cases, desiring to produce, is a statistical average (52).¹

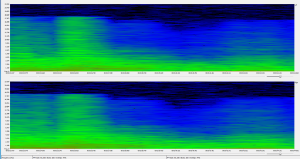

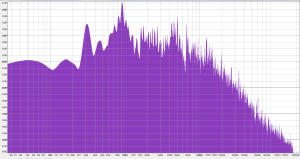

This spectral outlook does not necessarily vitiate or disenfranchise music. Composers instead argue that technical analysis opens up even broader vistas for sonic exploration because it allows music to be sculpted and directed to finer and finer degrees. Technical analysis cracks the shell of the listenable and demonstrates the subordination — and omnipresence — of the heard.² Here is a piece from Gérard Grisey, a prominent composer in the movement, entitled ‘Partiels’ (1975), which displays the thrust of this view. It’s a study of the attack and timbre of a trombone playing a low E2, wherein the instrument sounds that note and a group of strings and woodwinds follow, all mimicking the layers and shapes of its timbral patterns (‘Articulate Silences’). One note deconstructed and ponderously reassembled by 18 musicians.

Spectral analyses of ‘Partiels’

‘Partiels’ is part of a larger cycle named Les Espaces Acoustiques [Acoustic Spaces] — aptly named, not only for its breadth, each piece within taking several minutes to explore, étude-like, one particular aspect, but also for its attention to actual changes of pressure in space which an ear can register. Such spaces of this latter kind also exist in text. Print conventions create their own spaces which exert a special kind of pressure on the eye and its reception of content. Typeface, for example, places emphases which prefigure flow and direct reading, a paragraph too often signifies a unifying force of theme among its words. As Johanna Drucker might put it, narrative relies on diagrammatic configurations of text in space. She writes that coherent textual formatting — and inevitably, the content it houses — relies on a bundle of associations fortified by readers’ expectations, “made across, by recollection, probabilistically” (Diagrammatic Writing 6).³ What tools can those of us in the print sphere use to gauge the spaces and forces of a text’s visuality? Where are our analogues to spectral music’s frequency analyzers and spectrograms?

If, following these composers, music is “a special case of the general phenomenon of sound” (Fineberg), isn’t narrative a special instance of ink and paper, an arrangement of pixels on screen space? This is by no means a reductionist claim (or if it is, it, like spectral music, hones in close only to latter broaden); I’m only trying, as many have before me, to foreground a text’s materiality, to reiterate that “one can never find a perspective on a message free from the medium of its conveyance” (Dworkin 134).

– Dirty data –

Recent developments in topic modeling and text mining swerve dangerously close to forgetting the above claim. In one of his blog posts Ted Underwood lists six different uses for the method: categorizing documents, contrasting vocabulary, tracing the history of features (words or phrases), clustering features, entity extraction, and visualization (‘Where to start with text mining’). At no point does the textual object come into the (literal) equation, though from it all useable data is extracted. Underwood elsewhere writes, “When I started running LDA, I immediately discovered noise in my collection that had not previously been a problem. Running headers at the tops of pages, in particular, left traces: until I took out those headers, topics were suspiciously sensitive to the titles of volumes” (‘Topic modeling made just simple enough’). That he considers this a limit, not a venue for further exploration, reveals we literary critics’ continued prejudice against materiality. To echo Mowitt’s sentiment above, the scandal of big data is not that it creates noise, but that we persist in regarding noise as insubstantial and distracting, rather than a meaningful effect of the material conditions which “always produce an account of their own instantiation” in the transmission of that data (Dworkin 134).

And yet, at this moment digital humanists seem extremely well-equipped to collect and analyze the visual-objective rhetoric of the page, however apparently noisy, as we would any other source of information. In Macroanalysis Matthew Jockers makes a case for LDA topic modeling by citing a passage from Julia Flanders, saying the computer changes methodology, not as a “factual substantiator,” but “as a device that extends the range of our perceptions to phenomena too minutely disseminated for our ordinary reading” (27). This goes as much for the number of em spaces at the beginning of paragraphs as novels in a genre. If the “result of such macroscopic investigation is contextualization on an unprecedented scale” (27), there is nothing to stop us from considering, alongside topics and word cohorts, the kind of textual enframements Drucker emphasizes.

Can topic modeling or text mining register this attitude? How profoundly materialist can they be? Can they provide us with a psychophysical history of the — or perhaps just ‘a’ — book that eventually ends in narratological waters?† In addition to tracing Jane Austen’s prepositions (Burrows 1987) we should perhaps run probability analyses on her commas. What could a topic modeler, attuned to track all instances of the graphic, tell us about Laurence Stern’s favorite punctuation mark, the em dash? Can we go further than this and topic model word spacing? Typeface? Paragraphing? Gutters? Margins?

* * *

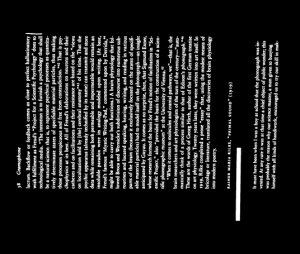

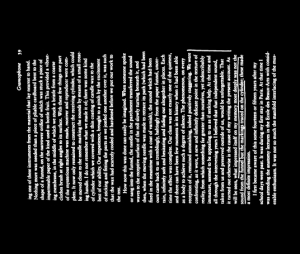

The specificities of one medium are often best explored by putting them into relief with another’s.‡ In preparation for a further study, I have taken BMP images of text and, using a program called Coagula Light, converted them into sound files (in a later post I hope to describe the particular way in which I chose to do this). The contours of the resultant sound file are shaped by lines of text but give us very little indication as to what those lines actually say. Still, this method registers the differences — and ultimately, their effects on reading — contained on a page. The sound file, if a bit noisy, lets us hear the text.

Kittler Noise (warning: loud file)

Images are from Friedrich Kittler’s Gramophone, Film, Typewriter

¹ While emphasizing the limits of physicality complicates the ideological division between listening and hearing, those categories, as we shall see in spectral music’s instrumentalization of those limits, remain instructive.

² Pressnitzer and McAdams write that spectral music, “in its search for expression through the material itself, without hidden or conventional reference, makes possible the recourse to certain data from acoustics and psychoacoustics not only to justify certain choices a posteriori, but also as a means of formalizing musical processes” (58). Mowitt’s comments above should put a damper on this idealist rhetoric. Does a broadening of the listenable break its hold and illusion, or only further solidify it?

³ “Above all the apparently static page must be understood as dynamic,” Drucker later explains. “The diagrammatic workings of relations across elements is crucial [to] the emergent and contingent identity and operation of any element or feature in the system” (26). Whether that element or feature be a name in a story or a box in a flowchart, it is subject to a graphical system — and that system’s rhetoric — in which “all is relational” (4).

† Pushed in this way, both would be able to articulate a single narrative’s shape to the finest degree while also revealing changes in the longue durée of general print conventions.

‡ This becomes possible in our digital age — and complicated. Craig Dworkin writes that a long-standing problem with structurally analyzing visual works is their lack of “discrete units of double articulation; the formal structure of a painting, for instance, had nothing neatly analogous to Western writing’s system of alphabetic letters and words. Digital imaging and analysis, however, provide the necessary unit of articulation: the pixel” (No Medium 96). Pixels are a double-edged blade: on one hand, they elide material specificity (perhaps only to reassert it later), on the other, they give us a shared language to articulate content.