George Eliot’s characters do not smile, they dimple. In August a team of researchers at MIT debuted an algorithm that reconstructs sound by analyzing the dimples sonic pressure imprints on bodies depicted in high-speed video. In 1877, tin foil captured Edison singing “Mary Had a Little Lamb” into his phonograph. Now, a plant in the corner, minutely battered by sonic waves, and video, running at 2,000 – 6,000 frames per second, can do the same, suggesting Steve Goodman’s ontology of vibrational force: “If we subtract human perception, everything moves. Anything static is only so at the level of perceptibility” (Sonic Warfare 83).¹ Eliot’s idiomatic description of smiling unintentionally proposes a reality of bodily affections 21st century R&D is now well-equipped to register. Perhaps this is what Dorothea felt in Middlemarch when she experienced the “weight of unintelligible Rome” with Mr. Casaubon, the pain of being “told that anything is very fine and not [being] able to feel that it is fine” (206).

History’s vibrations may be too much to handle for characters in Middlemarch, but the townspeople can easily detect tremors in their social milieu: they prefer the microcausalities of a parlor room over the echoes of the Past (capital P). The tragedy of Dorothea is that she feels neither. Eliot’s infinitely scalable omniscient narrator, on the other hand, spans both registers — and many more between. It can even hear the thoughts inside characters’ heads, delivering them as free indirect discourse for our eyes: “Dorothea said to herself that Mr Casaubon was the most interesting man she had ever seen . . . to reconstruct a past world, doubtless with a view to the highest purposes of truth – what a work to be in any way present at, to assist in, though only as a lamp-holder!” (18). This “ideal operator” of Victorian realism does just that, holding a lamp up to every one of its narrative’s minute details, functioning much like a high-speed camera. J. Hillis Miller’s article on the novel’s optic paradigm suggests a similar tendency. The dilations of this paradigm make every fact in Eliot’s “Study of Provincial Life” “a kind of multitudinous node which exists only arbitrarily as a single thing because we happen to have the microscope focused as we do” (“Optic and Semiotic in Middlemarch” 133). He explains that with “both gross and fine lenses” Eliot’s narrator sees and depicts the novel’s social medium through a “continual systole and diastole of inquiry” (135). The throbbing of “endlessly subdividable ‘minutiae’” finds an open ear in its panoptic omniscience (133).

I’ve intentionally mixed my metaphors. As Miller explains, gauging all these scaled complexes stretches the limits of narratorial powers, perhaps too thinly. An “imperialistic will to power” collides with a “fully developed subjectivism or perspectivism” (elsewhere, semiotic and optic paradigms duel [144]), putting omniscience at war with itself, detotalizing its totalizing impulse (136). Likewise, film operating in its ‘purest’ form at MIT — silently, with a superabundance of frames — falls into sound. These sonic vibrations researchers captured on film are a tenth of a micrometer long, which makes registering, and subsequently representing, such changes a formidable task. While a camera lens might be able to receive this phenomenon, the pixels used to show it on screen are entirely unsuited for the job. As a workaround, researchers developed an averaging technique which directly echoes spectral composition:

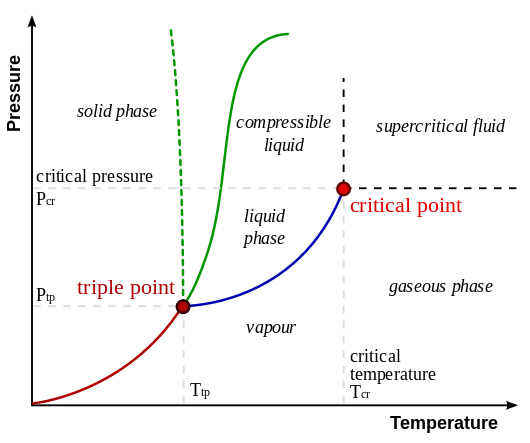

When a supercharged medium runs at full power, it creates, to borrow chemistry’s parlance, a kind of phase boundary, paradoxically obscuring its specific logic(s) and revealing the fuzziness of its contours, rather than showing its true colors. What is filmed in high definition is neither red, blue, or properly purple, even though these elements are precisely what a camera is meant to receive. Nor would it be, as of yet, correct to call this content sound. One medium is brought to a fever pitch only to surpass and upset the assumptions built up around its modus operandi. The corollary following McLuhan’s alignment of medium and message — “the ‘content’ of a medium is always another medium” (Understanding Media 8) — begins to look and act like différance. Kittler once said media are empty space between brackets (Discourse Networks, 1800/1900). These considerations suggest that the materiality I attempted to underscore in my last post is never stable to begin with.

Phase diagram. Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phase_diagram

In an interview with N. Katherine Hayles which touches, in part, on this issue, Lisa Gitelman remarks that materiality is “something that happens rather than something that exists” (“Materiality Has Always Been in Play”). This de-ontologizing, fragmenting gesture is a response to a brilliant comment previously made by Hayles: “materiality is a selective focus on certain physical aspects of an instantiated text that are foregrounded by a work’s construction, operation, and content. These properties cannot be determined in advance of the work by the critic or even the writer. Rather, they emerge from the interplay between the apparatus, the work, the writer, and the reader/user” (ibid).² In other words, materiality too is “a kind of multitudinous node which exists only arbitrarily as a single thing because we happen to have the microscope focused as we do” (Miller 133).³ As a thing that happens, it can be scalable, thematic, transmedial, and intersubjective.

Miller’s article shows this play need not only apply to texts which are explicitly concerned with materiality, or with media at all. As in media, so in theme: if we filmed Dorothea, tracked her every movement as Eliot’s narrator seems to do, at what point would an average pixel count (or sentiment analysis, for that matter) make it apparent she has fallen in love with Will Ladislaw? Would we say the same if we simply read events in the diegesis? My bets are on Chapter 62, when the latter visits the young widow and she, hearing his parting words, “sank into the chair, and for a few moments sat there like a statue, while images and emotions were hurrying upon her” (634). But it is important to remember that this ossifying judgment — and the narrational condition on which it is possible — comes post-factum, for “anything static is only so at the level of perceptibility” (Goodman 83). The process of her falling in love, and my (unconscious) attention to that process, is present in Middlemarch’s narrative long before page 634. Further, the term “love” fails to appear at this culminating moment and yet it does not, I think, fail to apply. Text-analysis will truly be radical when, instead of waiting on a list of topics (e.g., love), we examine in real-time how the micro-themes, tonalities, and sentiments of every word evolve — or mutate — into that list.† As Alan Liu has put, how then would we do either creative or theoretical work in a world where, depending on the flavor of topic modeler, we’ve moved from “Raskolnikov kills the old woman” to “Raskolnikov has an 82% chance of killing the old woman?” Up until Chapter 62, what were Dorothea’s chances of falling in love again? And which paradigmatic metaphor best casts a net over that love?

Like the minute pixel fluctuations in MIT’s video, these changes — either thematic or medial — are unimaginably small. In terms of information theory, very little in the way of new knowledge is added as they occur. In this view, then, it would be wrong to categorize these disturbances as noise (cf. my last post). Nonetheless, their ability to instantiate phase boundary effects proves to be quite disruptive to the stability of a given medium or narrative. The key problem in answering the above questions likely lies in the way we confront this play of low-information units.

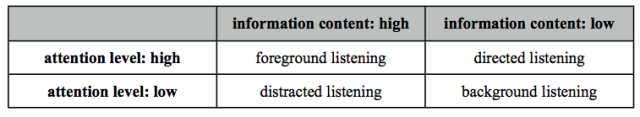

Salman Bakht proposes a schema of listening practices in “Noise, Nonsense, and the New Media Landscape” that maps out this issue quite well. His specific concerns revolve around the category of “nonsense,” a term he uses to describe certain non-semantic signals generated by the logic a medium imposes on its content. Not noise pure and simple, but a kind of medium-specific disturbance which accompanies perception.‡ To register nonsense, Bakht suggests a kind of “directed listening,” which would be akin to concentrating on the minute inflections a concert hall produces — sonic, spatial, or otherwise — instead of the symphony being played within. Below is his scheme:

While achieving an effective way to use directed listening remains a formidable task, at this initial moment Bakht’s formulation is a compelling method for tracking the periods in which materiality, broadly construed, enters a phase boundary. These phases, where the self-induced, contradictory defamiliarizations of a medium make formalized ontologies hazy, if not impossible, require precisely the kind of structural attention outlined above. As he understands it, directed listening displays medial logic; I would only add that it can likely identify places where and how that logic comes unravelled, how that logic is “something that happens rather than something that exists” (Gitelman). It may very well provide access to the “selective focus” Hayles finds in a text’s negotiations with its embodiment, or demonstrate the slightest alterations in pixel organization at MIT. Perhaps it can even signal the moment at which Dorothea finds herself in love once more.

¹ The vibrations the researchers’ camera detected are five thousandths of a pixel wide; unimaginably small compared to what our retinas can take in.

² Hayles later formalizes this statement into her theory of technotexts: “When a literary work interrogates the inscription technology that produces it, it mobilizes reflexive loops between its imaginative world and the material apparatus embodying that creation as a physical presence” (Writing Machines 25).

³ Eliot preempts both Hayles and Miller’s comments when she writes, “I at least have so much to do in unravelling certain human lots, and seeing how they were woven and interwoven, that all the light I can command must be concentrated on this particular web, and not dispersed over that tempting range of relevancies called the universe” (141). The light of her omniscience can only shine so bright and so far on Middlemarch’s social medium

† Narrative’s temporal structure immensely complicates this evolution. For the moment it is adequate to run and watch analyses on a detemporalized, unstructured database, content from Chapter 62 arbitrarily appearing near some from Chapter 5, but at some point we will need to develop a way to sync probability distribution with narrative’s temporal one. This will be a huge.

‡ Bakht cites Queneau’s Cent Mille Milliards de poèmes, an exploration of literature’s combinatory potential, and the Ebbinghaus experiments Kittler discusses in Discourse Networks, 1800/1900, which explored the capacity of human memory, as examples of this phenomenon.

Works Cited

- Bakht, Salman. “Noise, Nonsense, and the New Media Soundscape.” Canadian Electroacoustic Community. N.D. Web. 24 Nov. 2014.

- Goodman, Steve. Sonic Warfare: Sound, Affect, and the Ecology of Fear. Cambridge, MA: MIT, 2010. Print.

- Eliot, George. Middlemarch. London: Penguin, 2003. Print.

- Hardesty, Larry. “Extracting Audio from Visual Information.” MIT News. MIT News Office, 4 Aug. 2014. Web. 24 Nov. 2014.

- Hayles, N. Katherine. “Materiality Has Always Been in Play.” Interview by Lisa Gitelman. Materiality Has Always Been in Play: An Interview with N. Katherine Hayles. Iowa Journal of Cultural Studies, 2002. Web. 24 Nov. 2014. <http://www.uiowa.edu/~ijcs/mediation/hayles.htm>.

- _____, Writing Machines. Cambridge MA: The MIT Press, 2002.

- Kittler, Friedrich. Discourse Networks: 1800/1900. Stanford CA: Stanford University Press, 1990.

- McLuhan, Marshall. Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. Cambridge MA: The MIT Press, 1994.

- Miller, J. Hillis. “Optic and Semiotic In Middlemarch.” Ed. Jerome H. Buckley. The Worlds of Victorian Fiction. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 1975. 125-45. Print.